MerseyNewsLive opinion

At PMQs last week, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak admitted that the NHS is a big challenge to face but defended his party by saying that they’ve invested billions of pounds into clearing backlogs and providing more staff.

The Prime Minister referenced the 2019 manifesto, stating that he aims to build “a far stronger NHS” and he pointed out that there are 11,500 more nurses and doctors working in the NHS this year than last year.

But is the government really doing enough to help?

The Care Quality Commission recently released its annual ‘State of Care’ report. The report assesses health care and social care in England over the 2021/22 period.

The report investigates a series of hospitals and care facilities around England and includes the Cheshire and Merseyside regions.

The report finds that little progress has been made since its preceding report, highlighting that people with severe learning disabilities are not provided with the right care, that their rights are not understood, and they do not have access to specialist staff whilst the use of restrictive interventions remains high.

The report determines that the current state of care includes long waiting lists, a lack of commitment to guidance, inappropriate models of care, and a shortage of staff.

The report also notes that none of these concerns are new. Urgent changes are needed and that the Commission does not have faith that the government knows how to transfer care.

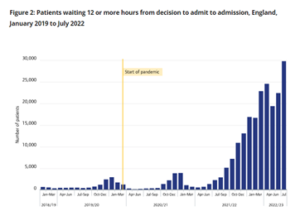

The numbers appear to back-up the findings.

In the period 2021-2022 some 24m people attended A&E, with one in five needing to wait at least four hours for treatment. The longest time to wait was almost a full day, 23 hours long.

In July 2022 alone, 29000 people waited 12 or more hours to be admitted to a ward from A&E and more than 45000 waited at least an hour to be handed over in March. The Commission believes that waiting for half an hour is too long.

Almost 13,000 people spent more time in hospital than was needed, because there was not the staff available to properly discharge them, meaning that these people were taking up valuable beds – through no fault of their own.

So, from the statistics, it’s clear to see that people face long waits and overcrowding, leaving their conditions at risk of worsening. There is a huge increase of patients waiting on a trolley in the emergency department because of a lack of beds. This spills over to affect ambulances as handovers are delayed, leaving ambulance crews to treat patients beyond the skill of what they’re trained for.

However, it’s hard gauge the human element from numbers. Healthwatch research aimed to investigate people’s experiences and two stories stood out.

“The first cancellation in July 2021, I was being wheeled down to surgery when they turned me around and took me back to the ward as no ICU bed available. They promised to do the surgery on July 26 2021 and would make sure no one took my bed. I started a week in isolation at home prior to surgery, only to receive a phone call three days before the procedure that it was cancelled and couldn’t give me another date. I have heard nothing since about another date.”

The second patient said: “My health and mobility is decreasing with every month that goes past. Without intervention, I will be wheelchair-bound instead of me walking the dog every day. I will soon need help with personal care, cleaning etc… because my conditions have not been adequately monitored and treated for 18 months.”

It’s clear that from the stats, investigation and personal accounts that the NHS is really struggling, despite the PM’s claims of billions of investment and an average of five new staff per hospital, per year.

The CQC report concludes: “We need to see reform, better investment in local support and service provision, and these changes based on evidence and up-to-date models of care.

“Urgent and emergency care services across England continue to be under immense pressure.”

Featured image credit: Chris Howells